Tag Archives: Katarina Zdjelar

Date: Sunday, 17 June 2012, Time: 4:45 – 7:15 p.m.

Location: Kriterion, Admission: €5, free with Cineville pass

Reservation required: 020-6231708 (Kriterion)

Participating artists: Artun Alaska Arasli, Neïl Beloufa, David Hammons, Coco Fusco and Paula Heredia, Moridja Kitenge Banza, Olaf Breuning, Tatiana Macedo, Sarah Vanagt, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Clemens von Wedemeyer and Katarina Zdjelar.

In an experimental and inquiring way, the videos presented in ‘Really Exotic?’ take us along on a visual, transcultural expedition in search of the exotic. The programme does not aim to find an ultimate proof or meaning of the exotic. Rather a variety of perspectives are brought together to show the multiple understandings and uses of this burdened concept. In each video a form of the exotic comes to the fore, but every time in a different environment and setting.

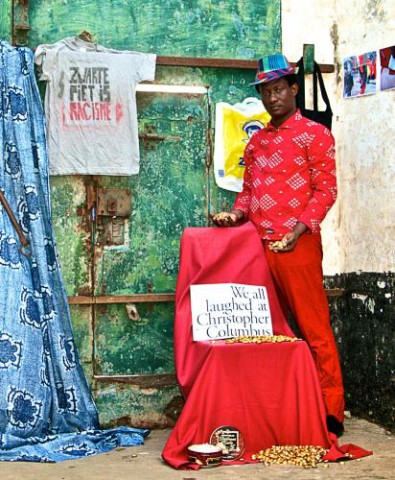

In the past, the exotic has been related to primitivism, the concept that, roughly speaking, entails an idealization of the unconscious and the original condition, captured in the image of the ‘noble savage’. This kind of exoticism is confronted with irony in works like Coco Fusco and Paula Heredia’s The Couple in the Cage: A Guatinaui Odyssey (1993) and Olaf Breuning’s Group (2001). Both mimic the primitive exotic by playing with and ridiculing the stereotypes that inform the primitivist imagination. Moridja Kitenge Banza’s Hymne à Nous (2008) caricatures the nineteenth century Europeans’ civilizing mission that aimed at transforming the purportedly primitive into the presumably civilized, by presenting an army of copies of themselves as the epitome of a ‘Europeanized’ African man. Irony directed at the primitive exotic is however just one of the strategies of alienation applied by the artists.

In his writing on exoticism in nineteenth and early twentieth century French literature, the philosopher Tzvetan Todorov exposes different forms of exoticism, but not all of them are based on an ominous ‘us’ versus ‘them’ scheme. With regard to the work of the French writer and ethnographer Victor Segalen, Todorov points to the ‘exotic experience’, a way of engaging (while traveling) with the unfamiliar from a point that presuppose an ‘us’ and ‘them’, a scheme departing from the proposition that without the ‘other’ the ‘self’ is incomplete. ‘Without identification,’ Todorov writes, ‘one does not know the other; without the bursting forth of difference, one loses oneself … one must be an exote to reconcile the two’. This kind of exoticism departs from the idea that, in the philosopher’s words, ‘the exotic experience is available to everyone; at the same time, it eludes the grasp of most. A child’s life begins with a progressive differentiation of subject and object; as a result, the whole world, in the beginning, seems exotic to the child’. Growing up entails an ‘automization of perception’, but everyone can revive the exotic experience by avoiding familiarity. As Todorov summarizes: ‘The common experience starts form strangeness and ends in familiarity. The exote’s special experience starts where the other ends – in familiarity – and leads toward strangeness’. The exotic experience is for Todorov thus an experience in which someone is estranged; it is a process of defamiliarization of oneself to the environment that is engendered.

The videos presented in this programme invite the public to indulge in strangeness, though the decision to provide the programme title with a question mark already points to the fact such an experience cannot be guaranteed, because it depends on the viewer, who needs to temporarily adopt the role of the exot. The exotic experience is, again in Todorov’s words, ‘much more [than naiveté or total ignorance] a matter of an unstable equilibrium between surprise and familiarity, between distancing and identification. The happiness of the exot is fragile: if he does not know the others well enough, he does not yet understand them; if he knows them too well, he no longer sees them. The exote cannot install himself in peace and quiet: no sooner does he attain that state his experience has already grown stale. No sooner does the exote arrive that he has to get ready to leave again; as Segalen said, he must cultivate nothing but alternation. That is perhaps why the rule of exoticism has often been converted from a precept for living into an artistic device: Chekhov’s ostranenie or Brecht’s Verfremdung (French: destanciation, English: “defamiliarization”)’.

In the ‘Really Exotic?’ programme, the exotic experience is understood as a benign form of exoticism, because it is based on a self-reflective and temporary ‘praise without knowledge’; worse forms of exoticism have led to, for instance, transformative missions of the exotic other or ideologically supported the colonisation of the other’s land. ‘The Really Exotic?’ programme takes Segalen’s conception of the exotic experience, as illuminated by Todorov, to its logical consequence and presents videos which look at everything differently. Because of the artist’s focus on detail, even that which is actually familiar to us can become unfamiliar. The artistic contribution to this programme takes us along on an exploration of an estranged environment that can at the same time be idealised and critically viewed.More