Author Archives: Tessa Verheul

Artists: Godfried Donkor, Abdoulaye Konaté, Wendelien van Oldenborgh, Willem de Rooij and Billie Zangewa.

Curated by Koyo Kouoh.

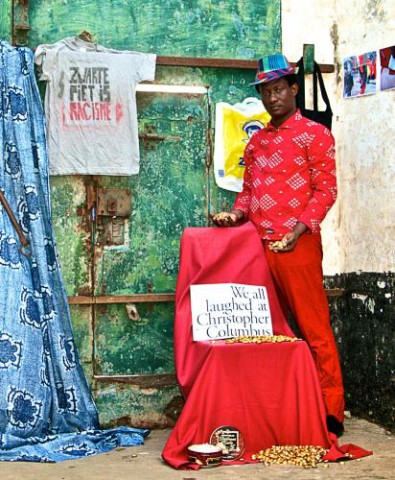

HOLLANDAISE is a critical, contemporary art exhibition built around the colourful printed fabrics that are exported from The Netherlands to Africa, and therefore popularly known as Hollandaise or Dutch Wax. Dutch textile enterprises such as Vlisco developed commercial applications for Javanese batik in the 19th century, and found their largest market in West Africa. Today the brightly coloured fabric is regarded as typically African. But in fact it is the result of complex globalization processes that right down to this day exhibit colonial features. Curator Koyo Kouoh, and director of her own art institution in Dakar, Senegal, invited five artists to delve into the phenomenon of Hollandaise and the peculiar trading relations and cultural interchanges that it represents. They all produced new work especially for this exhibition, which after Amsterdam will travel on to Dakar.

On the final day of ‘Time, Trade & Travel’ Zachary Formwalt was interviewed by art historian and critic Sven Lütticken. After a brief introduction to Formwalt’s artistic practice and interests, a fragment of his newest video ‘A Projective Geometry’ was screened. The video was also part of the exhibition ‘Time, Trade & Travel’ in SMBA. The film testifies to Formwalt’s investigation of the history of a railway in present-day Ghana. The railway was built in the 19th century by Britain to connect Sekondi to the inland gold mine in Tarkwa as a facility to create a connection with the worldwide market.

More

Anthropologist Rhoda Woets not only wrote an essay for SMBA Newsletter #129 on the work of kari-kacha seid’ou, she also lectured modern and contemporary Ghanaian art on September 30. During this afternoon Woets discussed the work of several artists in relation to the complex definition(s) of contemporary Ghanaian art. The notion of contemporary art in Ghana is for instance related to institutions such as art schools and art galleries. Popular art, craftwork and weaving such as kente are usually not included in this category.

The Ghanaian government has a tradition in stimulating the arts. In 1952, five years before the nation’s independence from the United Kingdom, the College of Art in Kumasi was established. Resonating its colonial relations, the school was affiliated with art institutions in London, such as Slade and the Royal College. Ghana’s first president Kwame Nkrumah continued many of these international connections, as he took Western culture as exemplary in his mission to create an independent nation-state. In his vision modern art was a tool to construct identity; he argued that artists should express Ghanaian cultural history in their work. Many Ghanaians indeed relied on African traditions and symbols in order to express their identity. One example of this concept of ‘Sankofa’ is the ‘Accra Optimist Club’, a group of Ghanaian men who wore traditional cloths during colonial times.

More

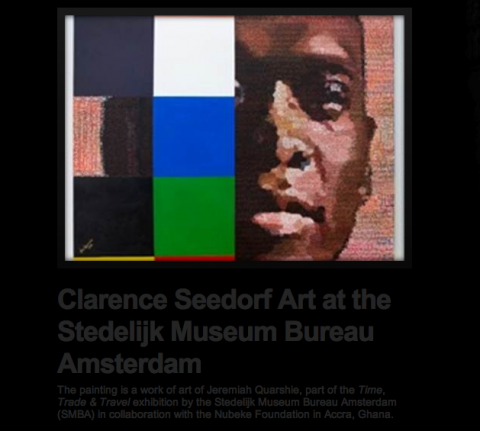

Soccer player Clarence Seedorf responds to the work of Jeremiah Quarshie on his personal website. As part of the exhibition ‘Time, Trade and Travel’ at Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam, Quarshie presents ‘This is who I am?’ (2012), including a portrait of Seedorf as a reference to postcolonial identity.

Click here to download SMBA Newsletter #129 and to read more on the work of Jeremiah Quarshie.

This summer the Dutch Museum Beelden aan Zee curated ‘Rainbow Nation’, an exhibition of contemporary South African sculptures. In the final weekend the symposium ‘Mixing the Colors of the Rainbow’ was organised, to discuss the current status of South African art and art history. Head of exhibitions Dick van Broekhuizen started the evening with a short introduction to ‘Rainbow Nation’. To provide a contextual framework guest curator Annelies Brans-Van der Straeten referred to the historical time line of the new art historical encyclopaedia ‘Visual Century. South African Art in Context 1907-2007’. Editors of ‘Visual Century’ Gavin Jantjes and Lize van Robbroeck were invited to explain the realization of this historical overview and the accompanying struggles with methodology. Dutch art historian and curator Esther Schreuder was invited to present her view on South African art history.

More

The Stedelijk Museum and Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam proudly presented the symposium ‘What is a Postcolonial Exhibition?’, an SMBA initiative organized as part of the program of Temporary Stedelijk 3 – Stedelijk @. Click here to read the symposium’s info sheet and watch the video registrations below.

What is a ‘Postcolonial Exhibition’? has been made possible through the support of:

Mondriaan Fund

Amsterdam Fund for the Arts

SNS REAAL Fonds

Part 1: Mapping the Field (turn up volume)

– Margriet Schavemaker, Head of Collections, Stedelijk Museum. Introduction and Welcome.

– Elena Sorokina, art historian and freelance curator. Introduction to exhibiting the postcolonial.

– Jelle Bouwhuis, Curator, SMBA. Brief note on the Stedelijk’s global art history.

– Johannes Fabian, Anthropologist. Introduction to Time and the Other, after interviewed by Anke Bangma, curator at the Tropenmuseum.

– Discussion

In collaboration with the Stedelijk Museum, Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam organized the symposium What is a ‘Postcolonial Exhibition’? on May 25. During this day the institutional engagement with the colonial past and the postcolonial present was discussed. The symposium presented a range of institutional practices and scholarly insights to examine a specific aspect: the exhibition itself and the exhibition strategies that go alongside it.

Curator Christel Vesters wrote an extensive report on the symposium.

A first impression, by Christel Vesters

What is a ‘Postcolonial Exhibition’? kicked-off with an introduction by co-organiser Elena Sorokina, who eloquently outlined the framework for the symposium by unpacking its two primary questions: ‘what constitutes the postcolonial today?’, and ‘what is the language of an exhibition?’ If an exhibition today is no longer merely a space in which objects are put on display but has developed itself as a trans-disciplinary, narrative space in which the parameters of time and space are no longer fixed, how can exhibitions then respond to developments like globalisation, post-colonialism or to our multicultural societies?

More

Date: Sunday, 17 June 2012, Time: 4:45 – 7:15 p.m.

Location: Kriterion, Admission: €5, free with Cineville pass

Reservation required: 020-6231708 (Kriterion)

Participating artists: Artun Alaska Arasli, Neïl Beloufa, David Hammons, Coco Fusco and Paula Heredia, Moridja Kitenge Banza, Olaf Breuning, Tatiana Macedo, Sarah Vanagt, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Clemens von Wedemeyer and Katarina Zdjelar.

In an experimental and inquiring way, the videos presented in ‘Really Exotic?’ take us along on a visual, transcultural expedition in search of the exotic. The programme does not aim to find an ultimate proof or meaning of the exotic. Rather a variety of perspectives are brought together to show the multiple understandings and uses of this burdened concept. In each video a form of the exotic comes to the fore, but every time in a different environment and setting.

In the past, the exotic has been related to primitivism, the concept that, roughly speaking, entails an idealization of the unconscious and the original condition, captured in the image of the ‘noble savage’. This kind of exoticism is confronted with irony in works like Coco Fusco and Paula Heredia’s The Couple in the Cage: A Guatinaui Odyssey (1993) and Olaf Breuning’s Group (2001). Both mimic the primitive exotic by playing with and ridiculing the stereotypes that inform the primitivist imagination. Moridja Kitenge Banza’s Hymne à Nous (2008) caricatures the nineteenth century Europeans’ civilizing mission that aimed at transforming the purportedly primitive into the presumably civilized, by presenting an army of copies of themselves as the epitome of a ‘Europeanized’ African man. Irony directed at the primitive exotic is however just one of the strategies of alienation applied by the artists.

In his writing on exoticism in nineteenth and early twentieth century French literature, the philosopher Tzvetan Todorov exposes different forms of exoticism, but not all of them are based on an ominous ‘us’ versus ‘them’ scheme. With regard to the work of the French writer and ethnographer Victor Segalen, Todorov points to the ‘exotic experience’, a way of engaging (while traveling) with the unfamiliar from a point that presuppose an ‘us’ and ‘them’, a scheme departing from the proposition that without the ‘other’ the ‘self’ is incomplete. ‘Without identification,’ Todorov writes, ‘one does not know the other; without the bursting forth of difference, one loses oneself … one must be an exote to reconcile the two’. This kind of exoticism departs from the idea that, in the philosopher’s words, ‘the exotic experience is available to everyone; at the same time, it eludes the grasp of most. A child’s life begins with a progressive differentiation of subject and object; as a result, the whole world, in the beginning, seems exotic to the child’. Growing up entails an ‘automization of perception’, but everyone can revive the exotic experience by avoiding familiarity. As Todorov summarizes: ‘The common experience starts form strangeness and ends in familiarity. The exote’s special experience starts where the other ends – in familiarity – and leads toward strangeness’. The exotic experience is for Todorov thus an experience in which someone is estranged; it is a process of defamiliarization of oneself to the environment that is engendered.

The videos presented in this programme invite the public to indulge in strangeness, though the decision to provide the programme title with a question mark already points to the fact such an experience cannot be guaranteed, because it depends on the viewer, who needs to temporarily adopt the role of the exot. The exotic experience is, again in Todorov’s words, ‘much more [than naiveté or total ignorance] a matter of an unstable equilibrium between surprise and familiarity, between distancing and identification. The happiness of the exot is fragile: if he does not know the others well enough, he does not yet understand them; if he knows them too well, he no longer sees them. The exote cannot install himself in peace and quiet: no sooner does he attain that state his experience has already grown stale. No sooner does the exote arrive that he has to get ready to leave again; as Segalen said, he must cultivate nothing but alternation. That is perhaps why the rule of exoticism has often been converted from a precept for living into an artistic device: Chekhov’s ostranenie or Brecht’s Verfremdung (French: destanciation, English: “defamiliarization”)’.

In the ‘Really Exotic?’ programme, the exotic experience is understood as a benign form of exoticism, because it is based on a self-reflective and temporary ‘praise without knowledge’; worse forms of exoticism have led to, for instance, transformative missions of the exotic other or ideologically supported the colonisation of the other’s land. ‘The Really Exotic?’ programme takes Segalen’s conception of the exotic experience, as illuminated by Todorov, to its logical consequence and presents videos which look at everything differently. Because of the artist’s focus on detail, even that which is actually familiar to us can become unfamiliar. The artistic contribution to this programme takes us along on an exploration of an estranged environment that can at the same time be idealised and critically viewed.More

Book presentation January 19, Rijksakademie Amsterdam

Report by Madelon van Schie

Book presentation Making Art Global, roundtable discussion with Annie Fletcher, Rachel Weiss, Direlia Lazo and Gerardo Mosquera.

The book presentation of Making Art Global (Part 1): The Third Havana Biennial 1989, with contributions by Rachel Weiss, Luis Camnitzer, Coco Fusco and Geeta Kapur ao, formed part of the program Temporary Stedelijk 3-Stedelijk@Rijksakademie and was organized in collaboration with publisher Afterall Books. Introduced by Annie Fletcher, editor Rachel Weiss and curator Gerardo Mosquera pointed out the groundbreaking aspects of the third Havana Biennial and clarified its context in two presentations and a roundtable discussion in which independent curator Direlia Lazo participated as well.

More

Mexican artist Erick Beltrán presents his project ‘The World Explained’ at Tropenmuseum Amsterdam. It consists of a large collection of interviews with so-called ‘non-experts’ on how the world functions. With a small team of anthropologists Beltrán interviewed people in Sao Paulo, Barcelona and Amsterdam. The conversations were recorded and transcribed and finally collected into an ‘Encyclopedia’, which visitors could take home. The accompanying maps and diagrams on the wall emphasise Beltrán’s theory on the production of knowledge as a local-based phenomenon.

‘The World Explained’ is on view until March 11. Click here to read a report in Dutch.

More

By publishing the Project ‘1975’ essay ‘The Politics of Exclusion’, SMBA presented an introduction to the range of problems connected to the definition of African Art. Author Rikki Wemega-Kwawu is certainly not alone in his criticism towards the current discourse of African and Global art. In addition the Nigeria-born American Sylvester Okwunodu Ogbechie, Associate Professor Art History at the University of California Santa Barbara, criticizes the ‘Eurocentric’ definition of contemporary art and the idea of ‘global contemporary’ in his article ‘Where is Africa in Global Contemporary Art?’ in Savvy Journal.

Okwunodu Ogbechie argues: ‘My estimate is that there are less than one thousand “Contemporary African artists” who live and work in the West although they account for 99 % of all artists included in international exhibitions of Contemporary African Art.’

Comparable to Wemega-Kwawu’s argument, Okwunodu Ogbechie states that the aspects of ‘transnational interaction’, to travel and communicate internationally, seem to be crucial in the definition of contemporary art. Yet, who has the facilities to perform this transnational interaction? And are the concepts of place, location and site-specific history of any value to the definition of African art? Click here to read Sylvester Okwunodu Ogbechie’s article ‘Where is Africa in Global Contemporary Art?’ in the online version of Savvy Journal (page 24-31).

Artist and writer Rikki Wemega-Kwawu wrote the sixth Project ‘1975’ ‘The Politics of Exclusion’. In this essay Wemega-Kwawu criticizes the fixation on Contemporary African Diaspora artists and the powerful position of curator Okwui Enwezor.

The Nigeria-born American curator Okwui Enwezor is often acknowledged as the representative of African art and artists. The first Johannesburg Biennale in 1997 and the Documenta XI in Kassel in 2002, are just two examples of the many exhibitions he organized. With these presentations and publications on the topic of African art, Enwezor played a crucial role in the production of a definition of contemporary African art. Wemega-Kwawu criticizes this definition in his Project ‘1975’ essay, as he signalizes an ‘Enwezor School’: a group of African artists, now living in the West, that are preferred and circulated well above their counterparts living in Africa. Wemega-Kwawu argues that Enwezor hereby defines contemporary African art by the artists’ experience of Diaspora: “as if nothing worthwhile is happening on the continent”. By the maintenance of this definition African artists living on the continent, are hindered to enter the international art scene. Click here to download Newsletter 125 ‘Tala Madani – The Jinn’ and to read Rikki Wemega-Kwawu’s essay ‘The Politics of Exclusion’.

Rikki Wemega-Kwawu (Ghana, 1959) lives and works as an artist and writer in Takordi, Ghana. He is alumnus of the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Maine, U.S.A. In 2008, he was an Adjunct Professor in Art at the New York University – Accra, Ghana Campus, where he taught ‘postcolonial studio practices’.