On the final day of ‘Time, Trade & Travel’ Zachary Formwalt was interviewed by art historian and critic Sven Lütticken. After a brief introduction to Formwalt’s artistic practice and interests, a fragment of his newest video ‘A Projective Geometry’ was screened. The video was also part of the exhibition ‘Time, Trade & Travel’ in SMBA. The film testifies to Formwalt’s investigation of the history of a railway in present-day Ghana. The railway was built in the 19th century by Britain to connect Sekondi to the inland gold mine in Tarkwa as a facility to create a connection with the worldwide market.

Lütticken described ‘A Projective Geometry’ as an extension of Formwalt’s previous works that all deal with economy in relation to materialism and immaterialism. With earlier works like ‘In Place of Capital’ (2009) or ‘Unsupported Transit’ (2011) Formwalt focused on the (un)representability of capital in relation to the invention of photography. ‘Unsupported Transit’ for instance, connects footage imagery of the construction site of the Koolhaas-designed Shenzhen Stock Exchange with a voice-over recalling Eadweard Muybridge’s experiment with time-lapse photography. Commissioned by American tycoon Leland Standford, who wanted to prove that there is a moment of unsupported transit in a horse gallop, Muybridge produced the famous horse pictures. Formwalt connects this description of time-lapse photography to Karl Marx’ notion of the ‘abbreviated form of capital’, in which capital appears to move of its own accord. Similarly, the construction of the Shenzhen Stock exchange seems to develop without any human intervention.

In ‘A Projective Geometry’ the extraction of capital (gold) is represented by the railway. As Lütticken remarked, the film distinguishes itself from the previous works insofar as Formwalt, besides the disembodied voice-over now also included his off-screen conversations with local people. In so doing he produced a new connection between on-screen and off-screen. The conversations took place when he was installing his camera to record the railway during the production process in Ghana. From the conversation we learn that the locals were suspecting the artist was installing surveying tools to measure the land like developers are used to do. Lütticken drew a critical connection between the railway developer in the 19th century and Formwalt, who each in their own time “plot the land”.

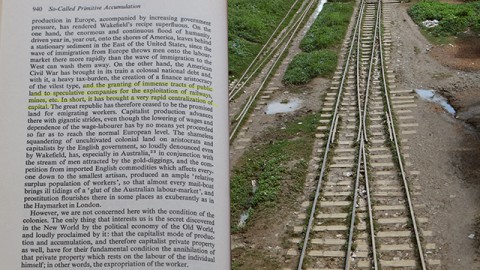

In ‘A Projective Geometry’, Formwalt combines a section from Marx’ Capital concerning his concept of ‘primitive accumulation’ with his recordings of the concerning railroad track in Ghana in a split-screen image. He explained that he was interested in the Marxist concept of the origin of capital and the accompanying (colonial) distinction between possessors and non-possessors, and compared it to the development of the railway. According to a 19th century document written by the British designer the new railway was going to develop the Ghanaian wasteland (“the virgin soil”) and to “give the people a reason to live”. This colonial paternalism is also expressed in the film ‘West Africa Calling’ (1927), a British educational production in which the development of Takoradi Harbor is documented. Commissioned by the British Conservative Party, the film functioned as a justification of the colonial project to the British workers and a visualization of the British (export) market. In this context Lütticken noted that even the stock market itself is a visualization, or a “prop”, of the abstract and invisible process of high finance.

A member of the audience then interpreted the railroads as a metaphor for history. On the one hand they represent a linear time development, while the multiple railroads express the parallelism between manifold histories and events. Lütticken finished the interview by asking Formwalt which history he represents in his work. Formwalt answered that he likes to represent small stories, one example is a petition in 1934 of the Ghanaian residents in which they expressed their disapproval to the British Railway Headquarters. However, the protest was simply ignored because the government judged the local population unqualified to have an opinion on matters of world economics. Formwalt found the residents’ petition letter and the British’s official’s dismissive response during his research in Ghana’s national archives in Accra; it became the point of departure for his production of ‘A Projective Geometry’.